Jewish Genes Are Not Enough

In our modern society, many who have been born with Jewish DNA seek farther and deeper when it comes to identifying as Jewish.

by Talia Carner

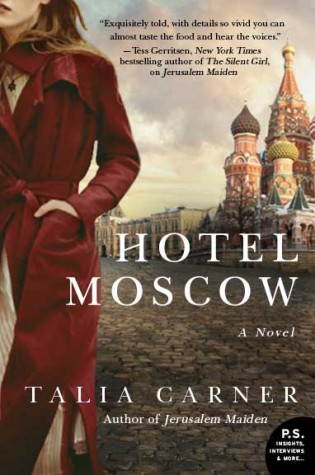

“She’s Jewish, the daughter of Holocaust survivors, who doesn’t want to be defined by the Holocaust,” is the way I have been describing the protagonist of my upcoming novel, Hotel Moscow. But what makes her Jewish? I kept asking myself this question throughout the long months and years it took me to shape my research material into a finished, suspenseful novel. Her story had to be psychologically nuanced; but how could I accomplish this goal if I was unable to define the phenomenon of being a secular American Jew?

There have been numerous attempts to label Jewishness as an ethnicity, culture, faith, religion, tradition, and race – or as a peoplehood rooted either in Jewish history or in the centrality of Israel to Jewish pride and identity. But in our modern society, many who have been born with Jewish DNA seek more: the inner connection, the spirituality, the self-definition that they fail to identify. The absence of such definition places secular Judaism into the vague category of “I will know it when I see it.”

Having been born in Israel to a secular family, my own Jewishness is deeply ingrained; it defines who I am. And, although my family did not strictly practice religion, which is the case with the vast majority of Jews in Israel, the country has an unmistakably Jewish culture. Even minor holidays are celebrated, almost reflexively: On Shavuot, an agrarian holiday that is rooted in the historical destruction of the Temple, people get together for a festive dairy meal of blintzes. Even if they do not light the Shabbat candles, it would be inconceivable for most of my friends not to have their adult children and their youngsters show up for Friday night dinner; and, if they must miss it, the family shows up for a heavy lunch on Saturday. I studied the Bible for 12 years and loved its richness of language, its grammatical contortions, and its poetic rhythm; however, since I had never been to synagogue, I was unaware that the dozens of passages I knew by heart were, in fact, prayers.

In my decades of living in New York, running a secular Jewish home, where God had no place, but Jewish values reigned, I continued observing my fellow American Jews. Some of my friends were active in Jewish causes. Some had visited Israel decades before, but had not maintained an eye towards the region. Some had attended yeshivas in their youth and knew Israeli songs, but had not visited the country. Some felt their Jewish identity awakened later in life, after it had lain dormant during their busy early adulthood years. Some friends went to a synagogue once a year, on Yom Kippur; others were highly involved in their respective congregations, asserting a strong connection. But a connection to what?

Unlike Christians, who often switch denominations when they feel uncomfortable with the beliefs or the practice of a particular branch of their religion, American Jews, I learned, often “give up” their religious affiliation altogether. The goyim, it seemed, had no problem identifying themselves. Only Jews – even those seemingly comfortable in their secular choices or their decision to have a “Christmas bush” – continued to struggle with questions of identity. While some have taken the easy leap from being an atheist to deserting Judaism altogether, others have acknowledged that the first does not necessarily lead to the latter: a Jew can be an unbeliever, yet feel Jewish. And, thus, the struggle continues.

Observing my fellow American Jews, what emerges most often is rarely expressed in words, yet bleeds through time and again: As much as secular Jews maintain a wide range of personal beliefs, Jewish values forever emerge, immune to the passage of time and winds of change. Even those of us who have left the religion cringe when a Jew is found guilty of a major crime, both because it somehow taints all other Jews’ reputations, but also because of the Jewish value of communal responsibility, as expressed by the talmudic phrase, “All of Israel are responsible for one another.” Conversely, even those who profess to no longer belong to the tribe often take covert pride in the fact that Jews have made unique contributions to the world.

I’ve seen ingrained Jewish values in the appreciation of education. The decree of Talmud Torah, or “wisdom study” has manifested itself in the fact that rare is the home of Jewish descendents that does not have books. When my youngest daughter was born, and I opened a college savings account for her, my non-Jewish friends were astounded at my priorities when facing economic hardships. Pressed in our discussion, most of the young mothers in my circle had no vision of higher education until the time came, if at all, and most did not expect their daughters to attend college. The only one who did had been born to a Jewish family that had converted, and had married a non-Jew and raised her children Catholic. Nevertheless, education was her top priority.

As the emphasis on education does not diminish among Jews who have little or no connection to the faith or tradition, the same can be said for the concept of tzedakah. It is so strong among secular American Jews, that every art, civic, humanitarian, or educational organization has a disproportionate percentage of Jewish philanthropists. When reading the names of supporters of either museums or relief projects, it is hard to believe that Jews make up barely 3 percent of the U.S. population. As all these causes are secular in nature, their donors must be motivated by the value of tzedakah.

Back to my protagonist Brooke: Having grown up in a sad home, she was “Holocausted-out.” For her, Jewish history had neither depth beyond the 1940s, nor a vision for the future. History was too present, too recent, too painful. It followed her in the bubble of air she was breathing. Although her mother had refused to practice religion until “God apologized for what he did to us,” Brooke sought Jewish spirituality by visiting a synagogue on Yom Kippur, but was turned off by fawning to God and His justice, while fearing His fury. She was too familiar with His wrath. Where could she turn for spirituality? New Age spiritualism, embraced by some Jews, such as shamanism, “sacred” scarves, Goddess Earth ceremonies, or mystical stones seemed to her so pagan.

It is in Moscow, when facing anti-Semitism, that my protagonist ultimately comes to terms with who she is. After years of running away from her Holocaust legacy “to remember” and her futile search for spirituality in a New York synagogue, for the first time, she feels pride in her Jewish heritage and flaunts her Star-of-David necklace. Finally, seemingly unaware of her deep-seated Jewish values, her greatest satisfaction is derived from helping others, from giving them what she has and they sorely need. It emerges in her willingness to actively “pursue justice,” risking her life in the process – and most of all, from her refusal to be vindictive when betrayed. Instead, helping her anti-Semitic protégé to safety brings home to Brooke the sense of who she is: a Jewish woman.

About the Author

Talia Carner was the publisher of Savvy Woman magazine. A former adjunct professor at Long Island University School of Management and a marketing consultant to Fortune 500 companies, she was also a volunteer counselor and lecturer for the Small Business Administration and a member of United States Information Agency (USIA) missions to Russia. She participated at the 1995 International Women’s Conference in Beijing, where she sat on economic panels and helped develop political campaigns for Indian and African women. Talia has written several award-winning novels, including Puppet Child (Mecox Hudson, 2002), China Doll (Windsprint Press, 2006), and Jerusalem Maiden (HarperCollins, 2011). Watch for her newest novel, Hotel Moscow (Harper Collins) in June 2015. Talia is a board member of the HBI, a research center for Jewish women’s life and culture at Brandeis University.

Talia Carner was the publisher of Savvy Woman magazine. A former adjunct professor at Long Island University School of Management and a marketing consultant to Fortune 500 companies, she was also a volunteer counselor and lecturer for the Small Business Administration and a member of United States Information Agency (USIA) missions to Russia. She participated at the 1995 International Women’s Conference in Beijing, where she sat on economic panels and helped develop political campaigns for Indian and African women. Talia has written several award-winning novels, including Puppet Child (Mecox Hudson, 2002), China Doll (Windsprint Press, 2006), and Jerusalem Maiden (HarperCollins, 2011). Watch for her newest novel, Hotel Moscow (Harper Collins) in June 2015. Talia is a board member of the HBI, a research center for Jewish women’s life and culture at Brandeis University.

To learn more about Talia Carner, visit www.taliacarner.com.

There are no comments yet, add one below.

Leave a Comment